カテゴリー 風刺画

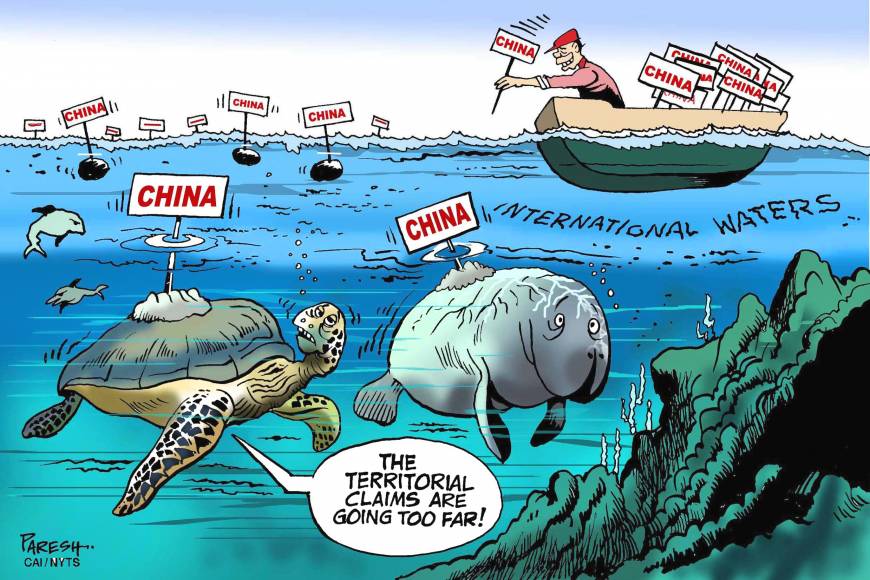

Japan and the South China Sea

Japan and the South China Sea

by Frank Ching

Hong Kong – For a country that believes strongly in noninterference in other countries’ internal affairs, China, oddly, is constantly telling other countries what they can and cannot talk about.

Last week, China again was putting on the pressure, this time on Japan, host of the Group of Seven foreign ministers’ meeting last Sunday and Monday in Hiroshima, as well as on the other participant countries, not to discuss South China Sea issues.

In March, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi publicly accused Japan of “double dealing,” saying Tokyo on one hand proclaims “nice things about wanting to improve relations,” but on the other hand “they are making trouble for China at every turn.” Clearly, talking about the South China Sea comes under the heading of “making trouble,” and Wang didn’t want Japan to put this issue on the agenda.

Wang continued his lobbying until the eve of the G-7 meeting, warning British Foreign Secretary Philip Hammond that the foreign ministers should not play up the South China Sea issue and telling his German counterpart, Frank-Walter Steinmeier, that discussing territorial issues would affect regional stability.

But the United States made it clear that South China Sea issues would be discussed. A State Department spokesman, Mark Toner, said that “any time we get together with our key partners we should be able to talk about the full range of issues,” the South China Sea is important, and “I would suggest that those topics should be on the table.”

What China wants is for other countries to stop talking about its island-building and militarization in the South China Sea. But if that cannot be entirely stopped, Beijing wants discussion kept to a low level and, preferably, not mentioned in any subsequent communique.

Thus, Xinhua, the state news agency, in a commentary accused Japan of planning “to place the South China Sea at the top of the agenda” at the G-7 meeting. Such a “provocation,” Xinhua said, would shift the focus of the meeting from more deserving concerns.

That seems unlikely. After all Japan, as the host country, chose to hold the meeting in Hiroshima, one of only two cities ever subjected to atomic bombing. The symbolic importance of the venue would focus attention on the need to prevent war, avoid conflicts, promote nuclear disarmament and counter proliferation. If there is an anti-China message hidden in there, maybe it is worth China’s while to reflect on it.

The foreign ministers’ meeting will be followed by the G-7 summit in May. Chinese diplomats may well find themselves busy for the next month, trying to influence the agenda of that meeting, which again will be hosted by Japan.

But then, China’s turn will come in September, when it will host the Group of 20 meeting in Hangzhou. At that time, China will be in a position to bestow or to withhold favors, including a one-on-one meeting between President Xi Jinping and Prime Minister Shinzo Abe.

Chinese Premier Li Keqiang declared last November in Seoul along with his Japanese and Korean counterparts that trilateral cooperation had been “completely restored” after holding a long-delayed China-Japan-Korean summit. He promised then that he would attend trilateral talks in Japan this year but, more recently, he has indicated that whether he participates or not will depend on Japan’s behavior.

Clearly, from China’s standpoint, Japan’s behavior so far has not been up to par because Li’s other pledges have not been implemented, including the resumption of visits by foreign ministers, the holding early in 2016 of a high-level economic dialogue and the resumption of talks on joint economic development in the East China Sea.

While accusing Japan of double dealing, China itself seems of two minds regarding Japan. While Wang accuses Japan of making trouble, others believe that Japan has made a fundamental decision to improve relations with China.

Thus, the Global Times newspaper discerned significance in Tokyo’s appointment last month of a new ambassador to Beijing, Yutaka Yokoi, a fluent Mandarin speaker with many years of experience dealing with China, unlike his two immediate predecessors.

Citing disputes over East China Sea islands, historical issues and visits to Yasukuni Shrine, the commentary said that those had occurred under the earlier ambassadors but, “from a long-term perspective,” the appointment of the new ambassador “shows a new approach in addressing these problems.”

But, of course, Japan’s foreign policy is not made only by one ambassador. A new diplomat is more likely to reflect changing policy than to make it. We will see soon enough if deep-seated differences can be resolved simply by picking a new ambassador.